Searching for a Splinter in a Smoke Stack

"I don't think we're going to make it, Max. I can't see a thing."

That was strange. There wasn't a cloud in the night sky, the usual Spring humidity was uncharacteristically low, and the upper atmospheric currents were reported to be unusually calm. It should have been a premier night for a trip out into the universe. But instead, looking through the port on our little spaceship of a telescope was like peering through a veil darkly.

We were, supposedly, off to image the Splinter Galaxy, or NGC 5907 for those of you into New General Catalog speak. It was Max who pointed out that all of our previous trips had been to galaxies with face-on, or nearly face-on, orientations. Grand design pinwheels. Wouldn't it be interesting to catch a galaxy edge-on, for a change? Well, NGC 5907 isn't nicknamed the "Splinter" galaxy for nothing. And so it was chosen, our destination for the night.

"Patience, Smitty. We have physics on our side."

"What are you talking about?" The frustration rising a bit in my voice. “I don’t see a thing!”

"Easy now,” said Max. "The Sun still rises in the East. The Earth still spins. Our telescope is aligned and correctly pointing at NGC 5907. We'll get there. It may take longer than usual, but we'll get there."

The problem was smoke. Wildfires in Canada, thousands of miles away.

We were trying to find a splinter in a smoke stack.

Recent high profile wildfires, like those in Los Angeles and the Grand Canyon, have spawned a lot of reporting in the popular media. A common thread running through most of these is that climate change is "increasing" wildfires. A reasonable take-away being: the frequency of wildfires is increasing; that is, common sense logic tells us that increasing temperatures, via global warming, is causing a greater number of wildfires. Here is an example in a piece, written by Ian Austen and Amy Graff, published in The New York Times on August 7, 2025:

Scientists have shown that warming global temperatures have greatly increased the chances of extreme fire weather, with more frequent and more intense wildfires as a result.

This common assertion that the frequency of wildfires is increasing is not born out by the data. More intense? Yes. More frequent? No.

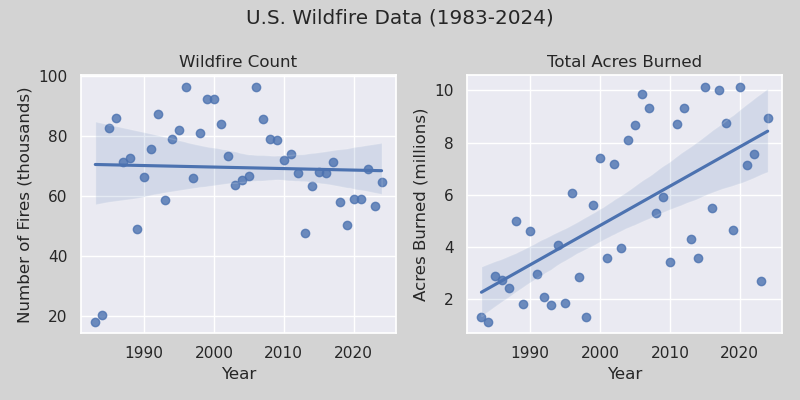

At least for the US, using data through 2024, this claim of an increasing number of fires is glaringly incorrect. As you can see in the left panel below, the absolute number of wildfires has not increased over the past 42 years. If anything the number of wildfires may have decreased slightly. Thanks, Smokey Bear!

What has increased is the size of those still-the-same number of fires. Check out the right panel. The average number of acres burned has quadrupled over the past 4 decades. Relentlessly; an increase of 2 million acres per decade. That is a lot more damage. That is a lot more smoke. There are 823 million acres of public and private forests and woodlands in the US. At that rate of increase, by the end of the century we’ll be burning down roughly 22 million acres, 3% of our woods, annually. Assuming things don’t get worse.

Okay. So what? Isn't this “number versus area” a distinction without a difference? I don’t think so. And here’s why.

If you can be convinced that the problem is just the number of fires, then we’re just witnessing a four-fold increase in carelessness. This “number of fires” view means we don’t have to take any actions against global warming. Because, obviously, that’s not the principal problem. The problem is careless cigarette smokers.

The problem is woke leftist radical Marxist fascist state governors who withhold fire-fighting water because they want their state’s cities to burn to the ground, and they hate America. That’s why they were elected by the citizens of their states in the first place. Obviously? Obvio ....

Camille von Kaenel and Annie Snider reported in Politico last January:

President Donald Trump declared victory on Friday in his long-running water war with California, boasting he sent billions of gallons south — but local officials say they narrowly prevented him from possibly flooding farms.

“Today, 1.6 billion gallons and, in 3 days, it will be 5.2 billion gallons. Everybody should be happy about this long fought Victory! I only wish they listened to me six years ago — There would have been no fire!” he said in a post on his social media site.

In the end, it was about 2.2 billion gallons. Victory? Well, let’s see. Ella Nilsen reported for CNN:

There are two major problems, water experts said: The newly released water will not flow to Los Angeles, and it is being wasted by being released during the wet winter season.

Hot on the heels of his “Victory” the President fired thousands of fire fighters in the U.S. Forest Service. Nice! Does the little left hand not know what the little right hand is doing? Apparently not.

The situation remains worrisome. ProPublica recently reported (July 22, 2025), “The Forest Service Claims It’s Fully Staffed for a Worsening Fire Season. Data Shows Thousands of Unfilled Jobs”:

DOGE cuts and voluntary resignations have severely hampered the agency as the nation enters the peak of fire season, with more than 1 million acres burning across 10 Western states.

The primary danger we face right now is not more fires, is not increasing numbers of fires, but rather bigger fires, quadruple-the-size fires. All the PR in the world isn’t going to help. Because the rate limiting step for new fires, ignition, isn’t increasing. It is the rapid spread of the fire afterward that is increasing. And that is definitely fueled by global warming.

This, I submit, is a distinction with a substantial difference.

William Herschel is credited with the discovery of the Splinter Galaxy on May 5, 1788, using an 18.7” reflector telescope. The galaxy is located about 46 million light years from Earth in the constellation Draco, the Dragon, and it is roughly 115 thousand light years across, similar in size to our Milky Way. Like Bode’s Galaxy, the Splinter Galaxy is a grand design spiral galaxy.

“Wait a minute, Max, NGC 5907 is only visible here on Earth from the perspective of its edge. From the side. How do we know it’s a spiral?”

“I’ve been there,” said Max. “Trust me, it’s a spiral.”

“Well, of course I do.”

But that’s only because the thick dust lanes around the outside edge of the galaxy, plus the bulge of light at the center, the nucleus, are characteristic of grand design galaxies. And speaking of dust lanes, the Herschel Space Observatory outreach website notes:

Cosmic dust consists of tiny particles of solid material floating around in the space between the stars. It is not the same as the dust you find in your house but more like smoke with small particles varying from collections of just a few molecules to grains of 0.1 mm in size.

So here we are, Max and I, in effect, searching for the smoke of the Splinter Galaxy, all while peering through a man-made stack of smoke coming from a fossil fuel barbeque.

"Look at this, Max! This is a three-minute exposure, for crying out loud. There are a few stars visible, but I don't see anything except maybe a super faint smudge of the Splinter Galaxy."

"Patience, Smitty," he repeated. "We have ..."

"… physics on our side. Yeah, you told me."

We put the telescope on cruise control and let it track our only mostly invisible Splinter Galaxy, taking consecutive exposures, all through the night. We didn't even stay to stargaze. It was a beautiful night but between the light pollution and the smoke screen there wasn't much joy to be gained from visual observation that night.

I looked around. And, as usual, Max had quietly disappeared.

He was right, of course. Physics was on our side. The telescope was correctly aimed at NGC 5907, and it tracked the Splinter Galaxy across the sky, capturing its photons to images all night long. In the morning, when those images were stacked, the Splinter Galaxy was there in all its edge-on glory, looking something like an alien spaceship. A fitting banner image for a smoky world, up there at the top of this post.

However, as it turns out, the Splinter Galaxy can dish out some rather powerful surprises, as we discovered while cruising about, taking in the sights.

But that’s another story.