Right on Time

The other night we had a colossal screw-up on a trip to photograph the Wizard Nebula. All because of time.

Last night the Gregorian modified artifact ticked over another numeral: 2024 became 2025. Right on time.

A human best-fit calendar estimation of true star time. A calendar so perfect, we must suffer an extra day in February every four years, except in years divisible by 100, unless that year is also divisible by 500. A time so perfect, the National Institutes of Standards and Technology (NIST) must sneak in a leap second every now and then just to keep “Coordinated Universal Time” (UTC) within +/-0.9 sec of “UT1” astronomical time. It isn’t all the fault of Pope Gregory XIII. The earth itself wobbles at times.

Time is strange. No two ways about it. We may think that time comes from our Garmin wristbands but, in fact, time comes from the stars themselves. You can take time off and ignore it completely. But if you are chasing galaxies around the universe, time becomes essential. Just ask Max and me.

The other night we had a colossal screw-up on a trip to photograph the Wizard Nebula. All because of time.

The Wizard Nebula is a massive cloud of luminous ionized gasses and dust residing in the Northern skies, within the borders of the constellation Cepheus. Over the past five million years, gravitational collapse within this gas and dust gave birth to numerous stars, which form an embedded open star cluster. The stars, in turn, blow stellar winds that shape the gas and charge the hydrogen which lights the nebula. The star at the center of the nebula, the main Hungadunga if you will, is pretty cool – because it isn’t one star. It is an “eclipsing binary” (HD 215835 or “DH Cephei”); two stars orbiting each other every 2.11 days. Imagine that for our Sun! In the banner image up top, DH Cephei is right in the center, but it is completely obscured by the brightness of the hydrogen ion emissions it drives by its radiation.

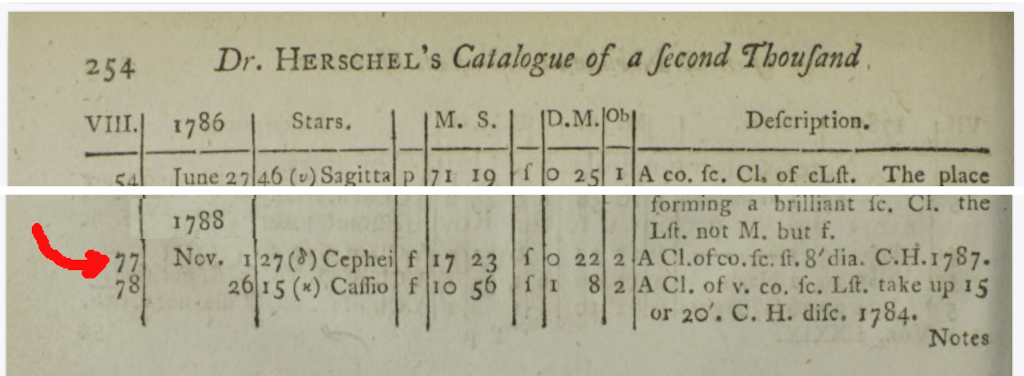

It was this open star cluster, not the nebula, that first caught the attention of astronomers. The first observation is attributed to Caroline Herschel in 1787. Of course, women weren’t supposed to be peaking through telescopes in those days but, fortunately for us, her famous brother, Dr. William Herschel, LL.D. F.R.S., cited her discovery in his paper “XX. Catalogue of a second Thousand of new Nebulae and Clusters of Stars; with a few introductory Remarks on the Construction of the Heavens.” It was published in 1789 in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Here is a clip from page 254 of a scanned copy of that paper:

Under class VIII, item 77, you see his description:

A Cl. of co. fc. ft. 8’ dia. C.H. 1787

which translates to:

A cluster of course scattered stars, 8 arcmin diameter. Caroline Herschel 1787

Pretty cool, eh?

Almost 100 years later, astronomer J.L.E. Dreyer published his paper, “New General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars,” an updated and extended version of the Herschel catalog. In Dreyer’s listing, the cluster is entered as number 7380 in the New General Catalogue, and it is now universally identified as NGC 7380. I should note that Dreyer was gracious enough to list “C.H.” under “Other Observers.” To this day, if you search for “Wizard Nebula” you will be taken to listings for “NGC 7380” which is an open star cluster. The Wizard was too faint and the nebula slipped under the telescope.

Shift time forward another roughly 65 years (your choice of clock) and Stewart Sharpless is in Flagstaff, Arizona, mapping the luminous clouds of ionized hydrogen gas (called “H II regions”) throughout the Milky Way. In his second catalog, published in 1958, our nebula finally gets a number: SH 2-142. In his notes for the entry Sharpless writes:

142. Part of II Cep association. Contains cluster NGC 7380.

The work of Sharpless and his colleagues was fundamental in determining the spiral structure of the Milky Way. He retired as Professor Emeritus, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Rochester. So this is personal.

NGC 7830/SH 2-142 continues to be actively studied, an average of two to three papers a year since 1970. Just last year, Singh et al. measured starlight polarization in NGC 7380 with the goal of characterizing the dynamics of its engulfing dust clouds. The first sentence of their paper is awesome:

Interstellar dust is responsible for starlight extinction, and their reemission in long wavelengths illuminates the Universe.

In order to correctly aim your telescope, you need to know in which direction it should be aimed. Seems obvious, no? But the Hotels-R-Us coordinates of all the choice cosmic resorts, like the Wizard Nebula, are playing a dizzying game with us as we spin about the axis of our little blue orb, Earth. The nebula might be up there at 52 degrees above the horizon, at about 319 degrees by the compass dial, but it is only going to be there on December 24, 2024 at 10:00PM EST, and then only if your home base is comparable to my backyard. If your telescope mount has the wrong time, it is guaranteed to end up as a pretzel trying to track the Wizard Nebula as it glides across the meridian.

And time is not just essential for those of us who congest the back of our scopes with cameras instead of eye pieces. If you are out with binoculars on a dark night, you can star-hop because your beginning star is right on time, just where you expect it to be. The iconic star map in your lap needs you to spin the central disk to align a date with a time. So even a timeless astronomer gathers some nebula, but good luck if you are specifically headed to see the Wizard.

Our little spaceship of a telescope is controlled by a single-board microcomputer. A ``Raspberry Pi 4’’ (RPi) to be precise. Like most of the community in amateur astrophotography, we are winging it here. You see, the RPi was never intended to have its own realtime clock. The designers imagined that an RPi would always be connected to the internet buzzing with network timestamp signals. Shortly after any RPi boots up, it shouts down the internet (affecting the accent of Network Time Protocols), “Hey! What time is it?” And the official time mavens of the internet then respond with the correct time to within 10 milliseconds.

But Max and I are out alone in a field, several times the distance beyond which the squared decrease in Wi-Fi signal can not survive. No internet. And so, without the helpful time mavens to wind the clock, the time on the RPi is whatever it was the last time it was shut down. Or maybe even something completely weird, like New Year’s Eve of 1970. Somehow we need to set the time on our solitary RPi.

The method we resorted to was all Maxie’s idea: we power up the RPi on its battery pack while still connected to the internet in the house. Once the RPi finds out what time it is, we disconnect the internet while still running the Pi on the battery pack, and carry the bundle out to the field to control the telescope mount. As long as the RPi keeps running we have an accurate system clock. Except, on the Wizard nebula trip? Max forgot to set the clock before we left.

“OK, Ok! We forgot to set the clock. Is that better?”

“Uhmmm .. ok … yeah. I forgot.”

The vestigial date on the RPi was off by weeks, not to mention broadcasting a bogus time of day. That night we wrangled a rogue telescope mount that behaved like a machine possessed. We zigged and zagged around the cosmos, completely lost and alone, photographing empty space, brilliant binary stars, unknown (at least by us), and almost lost it all in a primordial black hole; nothing visible but the Wicked Witch of the West flying round and round on a broomstick, screaming, “And your little Pi, too!”

Shaken up by the trauma of that trip, I looked around for a better solution to the RPi realtime clock problem. After all, this wasn’t likely to be the last time that Maxie -- I mean we -- would forget to set the clock.

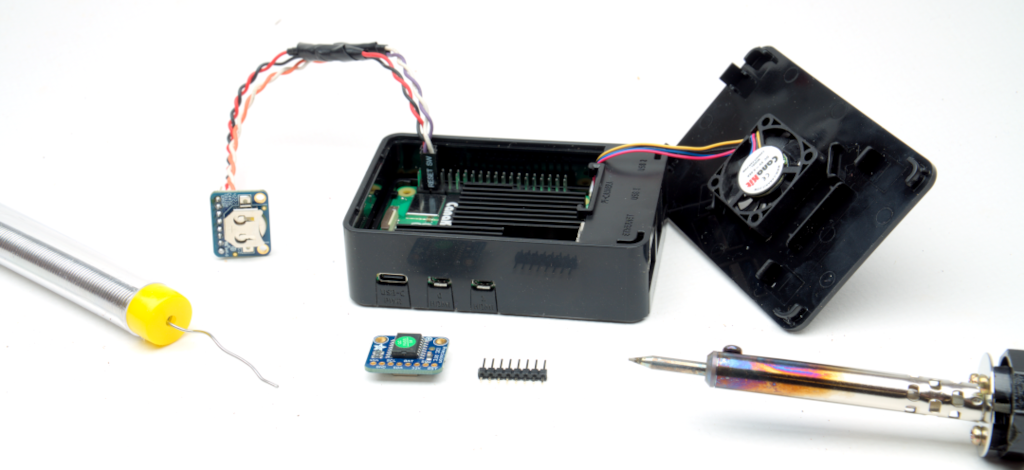

It turns out, the need for a realtime clock on the RPi isn’t unique to amateur spaceship telescopes. A lot of projects, like remote sensing applications, for example, are designed and built for places without internet connections. Consequently, there is a large community, both formal businesses like “Adafruit” and part-time Uncle George’s garage-based bistros, that cater to “Makers"/“Hackers” working with RPi and other single-board computers. If you want a realtime clock for your RPi, you can join the Makers and stick a teensy breakout board doohickey onto the RPi’s GPIO bus header. Whatever the heck that is.

Max decided we needed a “DS3231 Precision RTC.”

I went off to search through drawers of accumulated detritus looking for my ancient soldering iron.

The call for the DS3231-Ultra Mk-XIV module went out on the Szeriens’ communications network. It was urgent. Red flag.

The Szeriens are a race of “Makers” and “Creatives,” although those terms died out in the early decades of the 21st century, shortly after MuskBorg Inc. consolidated its control of world communications. How they did it was simple enough, ingenious even: communication satellites in low earth orbit. At first, the campaign was cloaked in the charity of bringing high speed internet to under-served rural and developing parts of the world. Then MuskBorg Inc. gradually bought control of the politicians, the social media platforms, and the regulatory agencies, eventually driving competing internet service providers into bankruptcy and oblivion – if they didn’t agree to be bought by MuskBorg Inc., that is.

There they were, sucking up government billions and continually hiking user fees, while decreasing speeds and reliability, extracting every ounce of value for Corporate and the Great Borg himself. And now, today, MuskBorg’s SmashLink is a giant reeking monopoly and the only legal ISP in the world. The Word always passes through MuskBorg’s ears.

Except for Szeriens. The Szeriens are Makers, remember, from a long line of hackers back to Archimedes. Over the centuries, the Szeriens built a vast mesh network of cheap communication repeaters that they make and deploy themselves, outside sanctioned MuskBorg channels. This Szerien network drives MuskBorg Inc. insane. The SmashLink satellites easily detect and locate the rebel transmitters, and MuskBorg is forever sending out shock troops to dismantle them. But there are so many redundant pathways in the mesh network that the Szeriens’ communications are seldom disrupted. And the relays are so simple and cheap to make that links can be replaced as fast as MuskBorg Inc. can destroy them.

In desperation, MuskBorg Inc. tried to gain a monopoly on the components needed to build the transmitters. But that was useless, and to this day, MuskBorg can’t figure out why their efforts are useless. They are useless, in fact, because of their own greed. In addition to communications, MuskBorg Inc. controls all land travel, which they do through their “autonomous driving vehicles,” so-called ADVs. “Taxis”, if you remember them. Private vehicles were outlawed many years ago, as illegal consumers of lithium. And so, now, you can only travel to destinations permitted by MuskBorg Inc., in MuskBorg ADVs, if you want to travel at all.

But the ADVs are fake! And they have been for several hundred years. For every four or five ADVs out there, some poor conscript is sitting in a MuskBorg Inc. sweatshop staring at a computer monitor so he or she can take over the driving from the bot and bail out the ADV when it is about to run over a pedestrian. Most of the time.

Szerien volunteers infiltrated the ranks of those workers long ago. When transmitter parts become scarce, or parts for any other Szerien technology, for that matter, an empty ADV mysteriously crashes into a nearby surveillance pole, and a posse of Szeriens quickly pounce and strip it bare. Wires, IC boards, microchips. Everything. Sometimes they leave the hull jacked up on cinder blocks; a meme MuskBorg Inc. has yet to figure out.

But the SmashLink satellites are now a serious problem on their own. In antiquity, there were only about 4000 of the obnoxious things whirling about the earth. Blinking like pawn shops and ruining astrophotography worldwide. But now, at any given time, there are over 200,000 of them, more or less, polluting the sky, bumping into themselves and other space rubbish, contributing to that rubbish. Ten thousand SmashLink satellites are now launched each day just to replace the ones in orbit that bricked themselves yesterday and decided to wreak havoc for eternity. In response, entire battalions of MuskBorg SmashLink Police now patrol low earth orbit in starsquads, preventing any citizen starship from traversing the satellite junk belt. “It’s for their own protection.” Because of course it is.

Then MuskBorg started coming after all of recorded knowledge. Anything that doesn’t fit with MuskBorg’s world view. Which is, “Me, me, me!” At first, the Newton papers were transferred to the Milky Way Archive without MuskBorg Inc. even knowing about it. The Verne papers were also transported successfully, but not without a wild chase around the world, through space junk, together with some primitive cloaking that fooled the MuskBorg goons. But the Asimov notes were almost lost. One Szerien was killed in the effort, blown up by the SmashLink Police while racing for the outer limits. She was a decoy, and the notes got through, but no one wants to risk repeating that strategy. And now the Einstein, Hawking, and Sagan data and notebooks are at serious risk of appropriation, and “disappearance,” by MuskBorg Inc. HQ. To be mangled, distorted, and presented as original, Fun-House mirrors MuskBorg research. History rewritten by the rich, for the adoration of the rich by the rich.

So Szerien Tech broadcast a call for the lost DS3231-Ultra Mk-XIV modules.

I found the soldering iron. Take great joy in small triumphs. The DS3231 is a cute little module about the size of a quarter. You can see a spare one, along with its breakout pin attachment gizmo, in the foreground of the image above. The RPi board is in the black case and the attached DS3231 is plugged into the GPIO bus pins, and is dangling precariously out in the void. Like any respectable bodge, the project consumed three yards of electricians tape.

There is a tiny lithium coin cell battery in the module, and once the time is set correctly the battery will keep it running, maintaining the correct time, even when the RPi is powered down. When the RPi is powered up again it shouts, “Hey, what time is it?” And the DS3231 replies, “Stop shouting! I’m right here.”

“The time is NOW”

A couple of DS3231-Ultra Mk-XIV modules showed up at the Astronomy Center shortly after the call went out. The Mk-XIV is a vast improvement over the original DS3231, which was often used as a realtime clock in old RPi’s back in the early 2000s. The Mk-XIV is a major upgrade. In addition to setting and maintaining time, the Mk-XIV can be activated to shift the experience of time forward, or backward, for the immediate space surrounding its location. Folklore has it the Mk-XIV sat as an unknown advancement for decades because it’s hacker/maker kept it a secret and then suddenly disappeared without a trace. Eventually, a curious Szerien discovered it in a garage together with largely accurate documentation.

The Mk-XIV installed in the starship was a beefed up model modified by the best hackers anywhere. The mods gave it extra power to timeshift a larger area. How large wasn’t known. With the MuskBorg gunships on the way, with orders to seize the notebooks, there had been no time to check the modifications. It was going to work, or it wasn’t.

The Szerien Low Earth Orbit Tracking Telescope (SLEOT2) records predicted a narrow window of time during which there would be a gap between the pieces of space junk large enough for the Szerien starship to escape. It was on its way. But it was a good bet the MuskBorg gunships were too.

“There they are.”

The gunships were closing. At least three of them. Looking like trashed Cybertrucks from an old movie. The first laser blast shook the Szerien starship. A quick maneuver placed a long-dead Chinese communications satellite in its path blocking the gunship. But that wasn’t going to work for long. “Hey! What time is it?”

“OK, it’s time. Activate!”

Nothing.

“Activate the DS!”

TIME!

A screeching one syllable metallic cracking sense of doom.

TIME!

What if the DS doesn’t work? What if we’re at the end? What happens when time ends?

There was another gunship laser strike. This time much closer.

TIME!

“For God’s sake Smitty!" Max screamed, “Activate the DS!"

TIME!

And then it was quiet.

Just a deep rumble, like the sound of a gigantic woofer at a rock concert, high up on the scaffolding, beating out root notes, and rattling your diaphragm. Long after the band left the stage.

The MuskBorg gunships were gone. Nothing but space junk flying by outside the port windows.

The DS worked! It did, didn’t it? Did I activate it? I must have done.

Maybe it was Max.

We began laughing hysterically. The junk gap was closing quickly, but we made it through, headed for the Wizard Nebula. Safe. With a cargo of human creativity that would never be stolen or suppressed.

Not if we had anything to do with it.

Time is precious.

The MuskBorgs of our time

are intent on stealing your time.

Of wasting your time

on meaningless distraction.

The theft of your time

means nothing to them,

because it adds nothing

to their time.

But the waste of your time

enriches them

by making you poorer.

Don’t.

Be the creative.

Be the maker.

Be the writer.

Keep your time close.

Then, when the time comes, we will be.

Right on time.