Keep It Forever With You

The wind whistled through the tack, rustling the straps on the luggage tied up top. It was not clear which was worse, the miles of rutted path, or the miles of mud threatening to suck the horseshoes right off the team straining to make forward progress. A sharp chill was in the air as the carriage made its 200 km journey from Brussels to Amsterdam. Not a moment too soon. Perhaps too late. 1585. And the Spanish had brought the Inquisition to Brussels uninvited.

Petrus Plancius shifted uneasily in his seat, suppressing visions of conflict, as the coach jostled onward. Theological studies in Germany, and later England, hard work, found him a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church in Brussels. Now all that was at risk. He was at risk. A soft target for an Inquisitor intent on rooting out heresy. All at an end. There was little choice but to flee the city for the safety of Amsterdam. He had gathered what he could transport by coach, but so much remained behind. So many books. Correspondence and more, sermons burned. He tallied the losses as the carriage rolled on, and the night wore thick.

Perhaps he should have stayed. Stayed in defiance. To defend theology. What would his God ask of him? William of Orange had fled Brussels, to continue the fight, and warned others to do the same. But Philip de Montmorency, Count of Horn, stayed in opposition. So too did Lamoral, Count of Egmont. Both were quickly arrested and convicted as traitors. Plancius shuddered at the memory of their beheading in the main square. And now William of Orange, even Orange, William the Silent, outlawed, had been assassinated in Delft. Silenced forever.

No, it was clearly best to flee. Was it not? What good a martyr? Still, a moral uncertainty. Still. Reason enough for Petrus Plancius to lift his eyes to the heavens, to the stars, forever after.

“Mon - o - cer - os”

“Doot doo, da doo doot.”

“Mon - o - cer - os”

“Doot doo dooo, doot.”

“Mon -“

“Whoa, whoa! Wait a minute, Max. Shouldn’t that be ‘Mahna Mahna’.”

“Doot doo, da doo doot.”

“Ok, Ok! Enough with the ear-worm. Where did you get the ‘Mahna Ceros’ thingy?”

“Well!” said Max, indignantly. “Some of my best friends are Monoceroses,”

“Monoceri?”

“Whatever. I’ve never been around more than one at a time.”

“Even one,” I added.

“Humpf. No, Dr. Smarty Pants. Unicorn! Monoceros is the Unicorn. And we’re off to visit the constellation Monoceros!”

I didn’t even know there was a constellation named Monoceros, let alone an asterism for a unicorn.

“That’s an odd choice for a constellation, isn’t it? It doesn’t seem to fit with Orion, Andromeda, Perseus, and all those other Arabic-Greeky-Romany myths that Ptolemy bequeathed to us.”

“Well, that’s because it isn’t!” said Max. “The constellation Monoceros was invented by the Dutch cartographer Petrus Plancius.”

Once in Amsterdam, Plancius settled in as preacher at the Dutch Reform Church. But he also began to engage his passion for maps, the stars, and navigation. Western Europe was on the move, colonizing, and these talents were in high demand.

Take navigation, for example. Anyone could determine latitude; latitude was easy and had been for ages. The elevation of the Sun above the horizon at noon names your latitude. There were tables for that.

But longitude? Longitude was hard. The career of a ship’s captain advanced, in part, through his skill at “dead reckoning,” the estimation of location from a combination of speed, direction, and elapsed time since the last “fix”, of which only elapsed time was close to a gold standard. And, unfortunately, errors made in the estimates of location would compound day after day, until the emphasis in dead reckoning risked being the “dead” part.

Whip out your trusty Silva compass and you will quickly encounter the phenomenon called “declination.” That arrow pointing to “North”? It’s actually pointing to magnetic North, of course, not celestial, or True North. The offset between the two is called ‘declination.’ Every good explorer, not using GPS to cheat, has to correct their compass for declination. When Max and I set up our telescope mount, we use a compass that is offset by about 9 degrees West to get a rough polar alignment.

“There are phone apps that will show you True North,” Max muttered.

“Yes, my Google Pixel 6 claims to do that. We tried it, remember? It was so inaccurate, we ended up in downtown Albuquerque along with Bugs.”

“Oh Yeah! Cool dude, Bugs!”

Anyway, Plancius tumbled to the fact that magnetic declination varies with longitude. And so he invented a new, more accurate, means of navigation. There were now tables for that. The method wasn’t foolproof. The differences in declination were small, and magnetic compasses of the time were just OK. But the improvement was enough to make Plancius a hero with the Dutch East India Company.

The Dutch East India Company was chartered in 1602, and Plantius was a founding investor. He had been making, and selling, maps and globes for some time, and in 1594 he even received a twelve-year exclusive patent from the government for making and distributing world maps. He made a ton of maps for the Dutch East India Company. Today, Rand McNally maps, NOAA marine maps, Google Maps, AAA Maps, YouNameIt Maps, they don’t show us the stars and constellations. That would seem silly nowadays. Who can see any stars, anyway. “Just the roads, Ma’am.” But in Plancius’ day, navigation depended on the stars, and so stars were expected on maps in locations dedicated to cosmography. Constellations mattered.

Now, there is nothing worse for selling maps and globes than having large blank spaces on them. And the old tricks of adding imaginary nymphs and sea monsters in those voids wasn’t quite working anymore. And the nymphs could get you into trouble with the authorities. No, the public wanted Science. So Plancius said, “What the heck,” and he just invented new constellations to fill in the empty realms of his maps. No one knows what Ptolemy thought of all this.

By 1612 Plancius had stuck at least 8 new constellations on a globe. One of those big blank spaces was next to the constellation Orion, the Hunter. A region with stars, but no assigned constellation. A region Ptolemy had ignored all those so many centuries before. A region just big enough for …

“A Monoceros!” shouted Max.

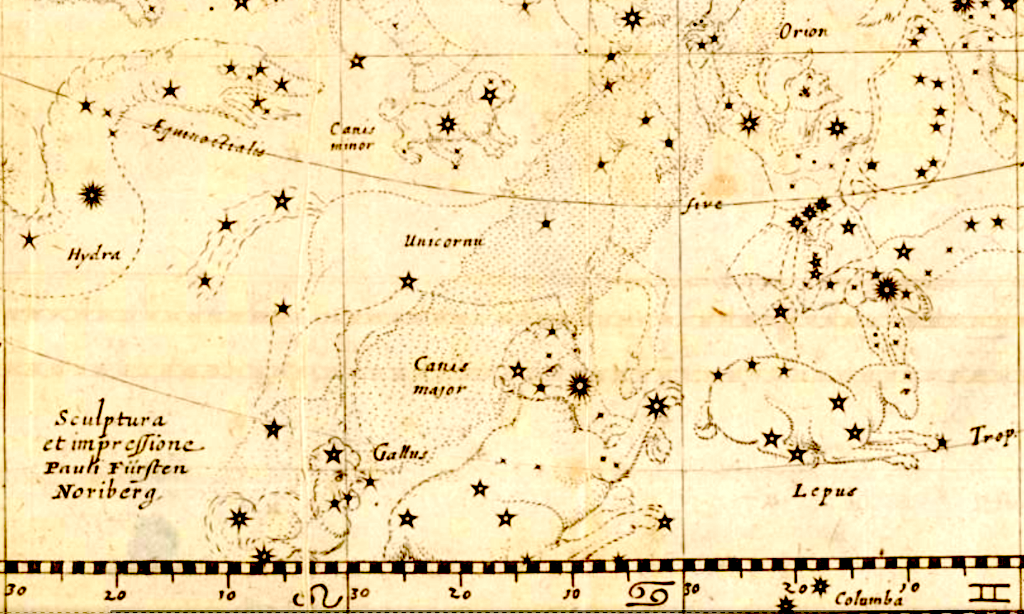

Yup, the Unicorn. And it stuck. The German astronomer, Jacob Bartschi, published a popular star chart in 1624 in which he actually labeled Monoceros as “Unicornu.” You can find Bartschi’s atlas online in the historical scientific literature collection at the Swiss ETH-Bibliothek Zürich. Here is a small swatch from the 1624 map. Unicornu is right there in the middle, trying to get Orion’s attention.

The cartographer Isaac Habrecht also kept Plancius’ constellations in his 1628 chart, but he reverted the name back to Monoceros, probably because Unicornu couldn’t be voiced to “Mahna Mahna.” Well, eventually everything in the modern world needs officiating and codifying. Thus, in 1922. at its General Assembly in Rome, the International Astronomical Union formally blessed Monoceros as one of our 88 official constellations. And here we are. Today, it is unlikely that anyone can muck with the constellations. At this point, probably not even Elon Musk could invent a constellation. Although, come to think of it, we do have the contemporary cartographic precedent of the “Gulf of America” forced into use, by a few, for that location of crude oil spills south of Louisiana. I suppose Musk could demand the IAU rename “Canis major” to “Doge” maybe? I must admit, I would pay good bitcoin for tickets to that show.

“So, where should we go in Monoceros?" I asked Max.

“Oh, that’s easy! The Rosette Nebula. It is fabulous!”

And so off we went over the course of three nights to explore and photograph a bit of Plancius’ imagination. You can find the results of our trip up there in the banner at the top of this post.

The Rosette Nebula is situated right near Unicorn’s neck, about 5000 light years from Earth. It is an emission nebula, like the Wizard Nebula from one of our previous trips, its hydrogen clouds ionized and glowing a gorgeous red, set off by rafts and filaments of dust, birthing stars everywhere. The intense radiation and solar winds whipped up by the cluster of young stars in its center have blown away the gases, creating a cavity within the core.

The scale of the Rosette is awesome to contemplate and almost impossible to imagine. It is roughly 130 light years across and occupies 2700 pixels in our original image. That means each tiny pixel holds the photons from an area of the Rosette of about 450 billion square kilometers. You would have to make 45 round trips from the Sun to Pluto and back just to simulate crossing that one single pixel’s virtual terrain once.

The Rosette Nebula stayed hidden in plain sight for most of its 5 million year history. It is a difficult target for visual astronomers because its light is spread over such a large area. Indeed, it was only the cluster of bright stars in the center that first gave it away. The British astronomer John Flamsteed is credited with the first report of the cluster in 1690. About the time Plancius was beginning to spin his globes. Herschel got in on the act too, of course, around 1784, and the cluster would eventually make it into Dreyer’s New General Catalog as NGC 2244.

It would take almost another 2 centuries after Flamsteed before German astronomer Albert Marth (1864), and American astronomer Lewis Swift (1865) independently reported weak nebulosity around Flamsteed’s NGC 2244 star cluster. Marth used a reflector telescope with a 4 foot mirror, while Swift used a refractor with a 16 inch objective lens. Swift’s observation became NGC 2237 and Marth’s became NGC 2238. Not to be outdone, Swift reported another weak nebula, which Dreyer cataloged as NGC 2246. So today, we have inherited a star cluster, with a bunch of associated nebula, all with their own data and numbers.

A current writeup in Deep-Sky Corner puts it this way:

The designation NGC 2239 is usually used for the Rosette Nebula, but this is not correct. Based on Dreyer's description, NGC 2239 is Herschel's star cluster and the designations related to the surrounding nebula are NGC 2237, NGC 2238 and NGC 2246.

And you’ll notice that star cluster NGC 2244, which started the whole thing, isn’t even mentioned.

For the record, a search for “Rosette Nebula” in kstars, a wonderful desktop planetarium program, selects NGC 2238 for its data coordinates. The same search in Stellarium, another great planetarium program, settles on NGC 2237, and helpfully suggests “Rosette A” as the star cluster NGC 2244.

“Max? You’re going to lose the audience! Why are you inflicting all these NGC somethings or others on me? ”

“Well, because there are so many of them, and none of them are it!”

“What’s the point, Max?”

“I guess ... that ambiguity and redundancy are important assets when hiding in plain sight.”

It took big hardware to finally uncover parts of the Rosette Nebula: Marth’s 4-foot mirror and Swifts 16-inch objective lens. It still takes big hardware for visual astronomy, the look-see, peek-through-an-eyepiece kind. In the March 2025 issue of Sky & Telescope, Howard Banich describes a detailed visual tour of the Rosette Nebula comparing his 8 inch and 30 inch reflector telescopes. Bottom line? He’s really skilled. And bigger is better.

What is remarkable, then, is that the banner image up top was captured with a little 3-inch refractor telescope. Through modern advances in cameras, digital sensors, electronics, tracking mounts, and image processing software – all the fruits of academic science and international R&D, which are both under current attack – Max and I can go deeper into space than Petrus Plancius could ever imagine.

It is not clear when or where it happened. Perhaps it was “an administrative error” in Maryland, sending a legal resident to the gulag in El Salvador. An error that the regime, in outright defiance of a US Supreme Court ruling, refuses to remedy.

It could have been Jensy Machado, on his way to work in Manassas, Virginia, or Julio Noriega, outside a pizza place in Chicago. Or maybe Jose Hermosillo, in Tucson, or Juan Carlos Lopez-Gomez, in Florida.

Maybe it was the little 2-year-old girl, or the 4-year-old boy with cancer, the 7-year old. Perhaps the 10-year-old cancer patient and her four siblings. Deported to Honduras, deported to Mexico.

It could have been in Arizona or New Mexico, with detainment of Navajo Nation peoples. Or at Ocean Seafood Depot in Newark, New Jersey, with a US military veteran. A plane held up in Djibouti on the way to South Sudan.

There is speculation it happened at Minnesota State University, Mankato. Or perhaps it was Rumeysa Ozturk at Tufts University, or Badar Khan Suri, at Georgetown University, Momodou Taal, at Cornell University. Or Yunseo Chung, Mahmoud Khalil, or Ranjani Srinivasan at Columbia University, Ranjani a postdoctoral student in the Department of Urban Planning.

Never trust the Department of Urban Planning; they might be advocating for the installation of multi-gender public Port-O-Potties.

In any case, no matter where the “where” of it happened, the “when” was surely 3 AM. A time timed for least resistance. For least preparedness. For least expectation.

The knock on the door.

“Open up! Open the door! OPEN THE DOOR NOW!”

An incessant knocking, for greatest confusion.

When the friends reached the door and opened it, they were confronted by six masked men, who pushed into the room. All in drab civilian clothes with no markings, bulging with bullet-proof Tevlar, they were brandishing military M16-style rifles and handguns.

“This is ICE. Unicorn, you are under arrest as an illegal alien. You are coming with us.”

“But Unicorn hasn’t done anything! Our friend! A citizen!”

“Come with us. Grokster! Get it out of here!”

“Where’s your warrant?” demanded one of the friends.

“Right here,” said the agent.

“I want to see it.”

“Buzz off, buddy! I’m not allowed to show it to you.”

“What are the charges,” demanded another.

“Well, weep weep, we’re not authorized to tell you that.”

“We demand to see a lawyer!”

“Ha! Say “Hi!” to him for me. Good luck with that. Come on, let’s go!”

They roughed hobbles around Unicorn’s legs and began to force their way out the door.

“Where are you going?”

But the kidnappers were no longer paying attention.

“Wait!” she cried. “No, wait!”

The ICE agents froze for a moment, caught off-guard, looked around, each expecting a decision from the other.

She ran to the Unicorn and offered a single red rose. The brilliant glow from the flower, its very fire, lit up the sky, for those who could see.

“A rosette,” she said. “An amulet. For protection against the madness of greed and ignorance. Keep it forever with you.”

The Dutch East India Company was arguably the world’s first multinational corporation. A test run for late-stage capitalism. It’s original 1602 government charter granted a 21-year monopoly on trade and commerce with Asia, and shares in the company were bought and sold on a fledgling Amsterdam Stock Exchange. The company functioned as its own government, authorized to detain and execute convicts, issue its own money, declare war, settle colonies in foreign lands, and negotiate and sign its own treaties. Much of its Asian infrastructure was built on slave labor, and the company’s ships, navigating by the light of Plancius’ grid lines, turned to the slave trade for profits.

The conflict between the young refugee Plancius fleeing Brussels, and corporate Plancius astride the Dutch Golden Age of commerce, may not have been totally lost on Reverend Plancius. Later in life he spent less and less time on cartography, and more and more time with his preaching. Still, a moral dilemma. Still.

Petrus Plancius left this world, his maps and globes and constellations, his pulpit, in 1622. What would his God ask of him? The Dutch East India Company outlived Plancius by 178 years, but slowly died of corruption, graft, and mismanagement. The Company eventually went bankrupt in 1800.

Only the unicorn has survived, still trying to get Orion’s attention. That, and the Rosette Nebula.

Keep it forever with you.