Jumpin' at the Woodside

Growing eggplant is the very definition of optimism.

Look at those eggplant transplants up there in the banner image! Beautiful aren’t they! I just set them out in the garden. So eager for life, for growth in the rich earth, to prosper and be fruitful.

Ah, they are so naive.

Eggplant is in the nightshade family, a cousin of the potato, pepper, and tomato. The first written references to eggplant date to some centuries B.C., and they suggest it was first used for medicinal purposes. It is thought to have been domesticated from a wild nightshade garden weed in East Asia, although the identity of this progenitor is still debated.

Nowadays, we deal with a native wild nightshade weed, Solanum carolinense, called "Carolina horse-nettle", which tends to set up shop anywhere and everywhere. It is distinguished by spiky prickles all over its leaves and stems. At least once a year I have to make the mistake of grabbing one with a bare hand. This Wikipedia entry sums it up:

It is an especially despised weed by gardeners who hand-weed, as the prickles tend to penetrate the skin and then break off when the plant is grasped. The deep root also makes it difficult to remove.

I had been pulling this “nettle” out of the garden for years before I learned it is not a nettle at all. And, as you probably will not be surprised to learn, it is not a horse either.

It is, indeed, an ambassador for the nightshades, and you can spot the family resemblance in its flowers, habit, and fruit. And its poisons:

While ingesting any part of the plant can cause fever, headache, scratchy throat, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, ingesting the fruit can cause abdominal pain, circulatory and respiratory depression, or even death.

It is also rather resistant to the broad spectrum herbicide glyphosate, a.k.a. "Roundup," which is pretty amazing, eh? Any living thing that can thumb its nose at Monsanto has earned my ever lasting respect.

My point is: the humans who first domesticated the eggplant must have been somewhat … um ... unusual.

My theory is that a couple of faculty dudes at a Chinese agricultural college, oh, say around 200 B.C., spent their entire careers, on a bet, trying to get rid of the spines on a nightshade weed. Then one Monday morning, they were trying to come up with a senior thesis project for a new undergraduate who was scheduled to show up that afternoon.

“Why don’t you have her breed nightshade into eggplant,” suggested the masochist of the pair. “That’s sure to fail.”

“Brilliant!” said the other. “We’ll give it to the undergraduate.”

And thus was born our modern eggplant.

Of course, it languished unnoticed in the medicine cabinet for centuries, until Parmesan cheese was invented in Reggio Amelia, Italy, sometime in the 13th century. But that’s another story.

In truth, the future is perilous for my poor little eggplant plants. The recurring result, to which I’m expecting a different outcome each year, is death by marauding flea beetles. My theory (my other theory) is that the locusts went on strike, and Mother Nature brought in flea beetles as scabs to cross the picket lines.

Flea beetles, you will probably not be surprised to learn, are not fleas. But, I am finally relieved to say, they are beetles. Ordinary irregular old fleas, order Siphonaptera, have historically garnered all the sensationalist headlines, fiction and non-fiction plot lines, and Fox News coverage over the years. They are noxious pests and a serious threat to public health.

Their claws keep them from being dislodged, and their mouthparts are adapted for piercing skin and sucking blood.

Icky.

Flea beetles are no such thing. They are rather run-of-the-mill pests, and only a threat to the health of eggplant. Well, that’s not quite true. There are many different flea beetle species (perhaps 9,900 to be inexact), and they have evolved specialized preferences in take-out restaurant menus.

My theory (my other other theory) is that The Great Flea Beetle Wars ended at the famous Conference of Pangaea, where the ambassador of everything, Marco of Floridus, informed the delegates, by tweet, that they were getting no more aid from the dinosaurs, and they should just pull themselves up by their bootstraps, divvy up the spoiled, and go their own ways. Whereupon, with the bootstrap thing, they became outstanding jumpers, and otherwise split the menu, and stiffed the bill.

Many peace-loving flea beetle species are beneficial insects, from a gardener’s point of view, and feed on unsuspecting weeds. However, one faction, after the edict of Floridus, decided to dine mainly on Brassica, such as cabbage and broccoli. Another, the George H. W. Bush faction, detesting broccoli, chose to live off the fat of the nightshades. In other words, my eggplant.

Flea beetles are called “flea” beetles because they jump like fleas. That makes a certain amount of common sense. Tell a flea beetle to jump, and the flea beetle will ask, “How far?” It can be pretty far! Depending on the species, a flea beetle can jump 100 to almost 300 times its body length. If you or I were gifted the talent to jump like a flea beetle, we could clear over a quarter mile. Leaping tall buildings in a single bound, as the comic books foretold. Handily winning gold in the Olympic long jump.

Scientists have been studying this amazing leaping ability of flea beetles for going on a hundred years now. S. Maclik, F.R.Z., described the “inflated” (i.e. big) hind femur of the flea beetle in a 1929 paper published in the Journal of Zoology. This paper is so important to the world that the publisher, Wiley, keeps it behind a paywall. You can rent the content online for 48 hours, at $16.00, or buy a PDF copy of the paper for $62.00. Before tariffs.

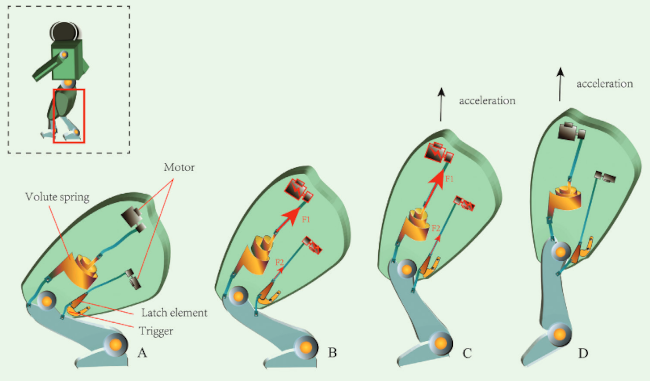

But flea beetle mechanics is not a dead language. Just recently, Yongying Ruan et al., an international team of Chinese and U.S. scientists, recently used high-speed photography, micro-CT scans, and 3D modeling to elucidate this jumping bio-mechanism in more detail. It turns out, the big old femur houses a big old “spring” that, when tripped, catapults the beetle up, up, and away. The title of their 2020 paper says it all: “The jumping mechanism of flea beetles (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Alticini), its application to bionics and preliminary design for a robotic jumping leg.” They aren’t kidding either!

If designed using a catapult mechanism, a jumping leg could propel a robot into the air in an explosive manner (Fig. 6), while the robot could also return to a regular walking mode at any time by the catapult mechanism being switched off, such as a flea beetle does. A preliminary design of a robotic jumping leg is given in Figure 6.

Here's a snippet of their Figure 6:

Just wind up the volute spring with a motor, pull the latch element to activate the trigger, and BANG, over the mote and into the castle. Match a set of these guys with AI and the world is your broccoli. Or eggplant, if you prefer.

I will leave you with visions of giant mechanical bionic flea beetles bounding across the battlefield, trampling mechanical bionic Tesla Cybertrucks as they go.

And, with a little luck, the tiny, rather cute, biological flea beetles will leave me with some eggplant in exchange for this publicity.