Happy New Year, Spinach!

Ten days on from the Winter solstice and I imagine the days are staying lighter just a shade longer. If they aren't, they should be. The truth is today, the first day of 2026, will have 36 seconds more daylight than the last day of 2025. I guess that's a shade.

It was a cold New Year's morning; below freezing most of the night. As the day warmed, I went out to the garden and opened the winter beds protected by row cover. I have a few garden crops that will thrive through the winter. Most winters. Crops that are actually worth tending to with ice-cold fingers. My fingers, not the crops. Spinach is one of them.

"Happy New Year, Spinach!"

The power of the comma. Later in the day it would be "Happy New Year spinach" instead. Spinach for the New Year's kitchen table.

The tuxedo name for spinach is Spinacia oleracea and it has its own dedicated genomic database, SpinachBase. Spinach sports a diploid genome with six pairs of chromosomes comprising roughly 989 million base pairs. For context, we humans are walking around with about 3.2 billion base pairs. That is, our genome is only a little more than 3 times the size of spinach. That would seem to explain a lot given the current state of human affairs.

Both historical horticulture and genetic analysis point to Persia as the originating spinach basket of the world. My personal mythology attributes the breeding of modern spinach to the two great Persian Iyam godesses, Iyam Wat Iyams and Dhats Als Iyam, each contributing a point of departure to the program. The first was when two wild spinach parents, S. tetrandra and S. turkestanica, diverged from one another an estimated 6.3 million years ago. No doubt while arguing over the proper ingredients for Borani. The second was about 0.8 million years ago when S. oleracea separated from S. turkestanica and began exploiting the local humans to do for it all the hard work of growing up.

Here's a family portrait from a 2024 paper by She et al. where this was all worked out using genomics and DNA sequence analysis:

Decendents of both wild species are still with us. S. turkestanica has 19 observations in the iNaturalist database, all in and around the Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan regions, while S. tetrandra has been reported only twice, further west in the Republic of Dagestan, Russia.

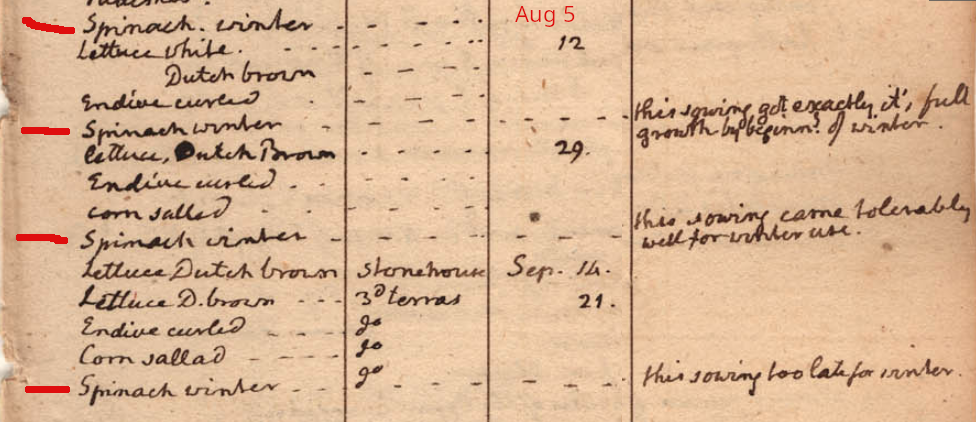

My winter spinach beds follow along in an illustrious tradition. Just up the road at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson planted spinach from August through September for his winter garden. A variety now called "Prickly-seeded Spinach." And TJ wrote it down. Here is a snippet from his "Garden Book" for the year 1811:

You can see I've highlight four entries for "Spinach winter" in red, which Jefferson sowed on August 5, 12, 29, and September 21. Only three plantings on all of page 43 merit "miscellaneous" comments; all three for the spinach plantings you see in the snippet above. For the "Spinach winter" entry on August 29, Jefferson notes:

this sowing came tolerably well for winter use.

That fits with my experience. Tolerably well.

There are a lot of spinach varieties for the home garden. Johnny's 2026 catalog lists 6 "smooth-leaf" varieties, and 7 "savoy-leaf" varieties. I have always preferred the savoy varieties, but you don't see them very often in the grocery stores anymore. Uprising Seeds has the explanation:

...the modern industrial food system has little use for the deep ruffles and folds of these types. As a baby leaf, it is harder to clean, making it inconvenient to process for "ready-to-eat salad" bags; for bunching by the case, the volume of the leaves makes it difficult for tidy bundling and takes up too much room in the box.

Phooey on that. The variety I grow, pictured in the banner image up top, is "Winter Bloomsdale," sourced from Southern Exposure Seed Exchange. Uprising Seeds describe it as "a vigorous winter-hardy selection from the once venerable Bloomsdale lineage." That lineage goes back to one of the first commercial seed companies, D. Landrath & Company, Philadelphia. Landrath released "Bloomsdale" in 1826. "Winter Bloomsdale" was probably maintained or resurrected in numerous places, but notably on the Olympic Peninsula a couple of decades ago or more.

And the beat goes on. "Abundant Bloomsdale" is a recent variety from a traditional cross between "Winter Bloomsdale" and "Evergreen" (Ark 88-212), a variety with increased resistance to white rust, a nasty fungal-like disease of spinach. You can read about the breeding plan at the Organic Seed Alliance website to get a feel for the work involved. "Abundant Bloomsdale" does very well in my garden. But for winter? I'll stick with "Winter Bloomsdale."

The elegance of spinach fresh from the garden will never grace enough kitchen tables. Which is sad, because store-bought canned spinach is the dregs of the green vegetable pit. Popeye glopping a glop of spinach goop sprung from a can is cartoonish, for sure, but correctly tags the wet, sloppy, tasteless, tooth clogging nothingness previously known as spinach. I imagine that Popeye had fresh spinach once upon a time. And remembers. So now his muscles bulge and he beats the crap out of the Bad Guys as a protest against the drab canned stuff the animation staff insists that he inhale.

Even the plastic bagged microgreen baby smooth-leaf stuff, lining the upscale grocery stores for today's Yuppies, spinach trucked all the way from California for the refrigerated produce shelf, and no doubt all the way back again for the Californians, even that doesn't come close to freshly picked, right out of garden on New Year's day, spinach.

That's a treat for which you have to self employ.

Happy New Year, Spinach!