Autumn's Swan Song

Happy Thanksgiving.

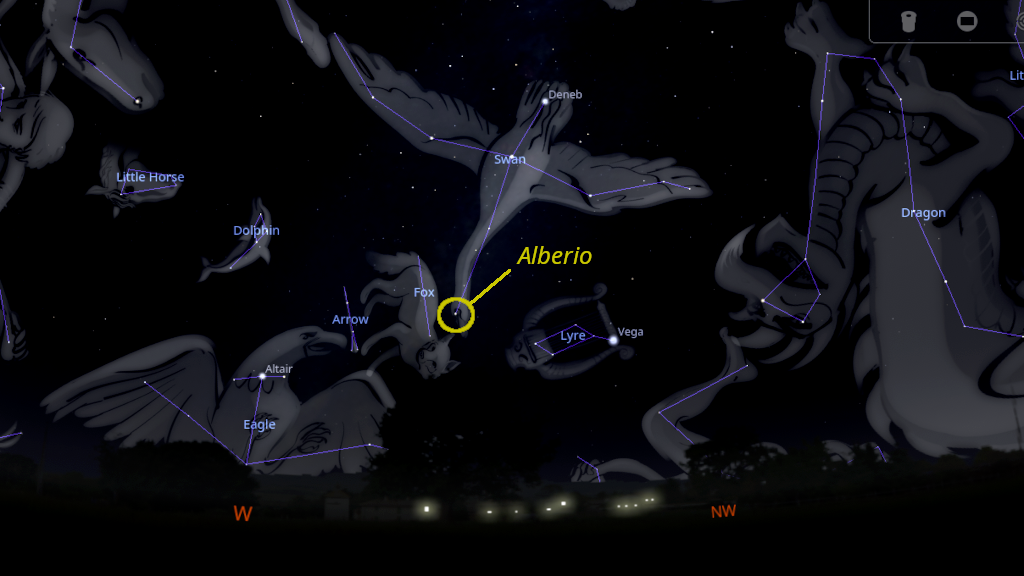

Albireo is the 5th brightest star in the constellation Cygnus, the Swan. This time of year, in the early evening, Cygnus is rapidly disappearing below the Western horizon, with Alberio – at its eye, or beak, depending on the cartographer – out front in the lead. Like snow geese headed South in their annual migration. At my location near Charlottesville, Albireo will be lost from the night sky completely by late December, not to return again until early June.

With the departure of Cygnus, daylight has become a noticeably scarcer commodity. The hours of sunlight here shrank to less than 10 just a week or so ago. And it will continue to recede with determination until the Winter solstice.

Most of my garden has been put to bed, losing out to the frosts of October. Winter rye, seeded in late August, is now a thick cover crop, relaxing over the former vegetable real estate. Some of my favorite winter crops, like kale and spinach, are safely under cover. Safely, that is, baring a prolonged appearance of single digit temperatures. But even the kale are hibernating, hunkered down for the duration, waiting for the return of a less impatient Sun before resuming growth in February.

So it is not a coincidence that we celebrate Thanksgiving this time of year. The months ahead are traditionally a challenge for agriculture and industry. By pausing to calculate, take stock, and give thanks for what is in hand, thanks for friendships and connections, we find a simple way of gathering strength and sharing it.

Look up at Cygnus, and Albireo is a bright magnitude 3 star, visible even with modest light pollution. It is the single dot, circled, in the banner image up top. But look closer, with binoculars or a small telescope, and Albireo splits in two. It is, in fact, a double star, and one of the prettiest there is. A brilliant gold/yellow star, Albireo A, and a fainter blue star, Albireo B, separated by about 34 arc seconds. For context, it would take roughly 50 Albireo pairs to span the diameter of the moon as viewed from earth.

Formally, Albireo A and B could comprise a gravitational bound pair of stars in orbit or, instead, they could simply be an optical double – unrelated stars that look like a double because of our perspective. The distances to both stars were measured by the wonderful, late, Gaia space telescope, and the answer is … we can't tell. The inherent errors in the measurements are too large to answer the question. I like this ambiguity. I'm sure it will be resolved one day soon but in the meantime it puts a skip in my step.

So. Albireo: a beautiful double star. Yes?

Look even closer, with spectroscopy, interferometry, photometry, and very large telescopes – way beyond what Max and I can fly. Look closer and that one star, Albireo A, turns out to be not one, but three stars in a gravitational bound system. Three stars orbiting each other in a mad dash.

So Albireo, the single star we see by eye, is actually a double star, is actually a quadruplet star system. Multiple facets making up the eye of Cygnus, the Swan.

Albireo can be thankful for all the stars in its cluster, for without them there would be no Albireo. And Cygnus can be thankful for Albireo, Deneb, and all the other stars far out around it, for without them there would be no Cygnus.

And we can be thankful for each other, for without us? Well, for one thing, there would be no one to see Albireo.